| |

Por Sabrina Mazzali-Lurati & Peter Schulz

Número 38

Abstract

The increasing importance of semiotic analysis of new media is well

acknowledged. In our paper we concentrate on the process of interpretation

and comprehension of hypertextual transpositions. Hypertextual transpositions

are a particular kind of hypermedia for literature and literary

studies. In our research we aimed at understanding if and how the

characteristics of the hypertextual form (namely, the fragmentation

of contents and the absence of a predefined reading order) have

an impact upon the act of reading. Such a question is central as

to the improvement of the effectiveness in the use of this kind

of artefacts. After having introduced the topic and the general

framework, we will provide a definition of hypertextual transpositions.

In the main part of the article we will outline and describe the

two main features of this kind of hypermedial applications (namely,

the logic of representation and the second order representation),

taking care to point out their impact upon the user’s act

of reading and comprehending the application contents.

Keywords:

semiotics, new media and hypertext studies, text comprehension.

0.

Introduction

0.1 Semiotics and new media

On

the borderline between semiotics and informatics stays the study

of the process of interpretation and comprehension of new media

artefacts, such as hypertexts and hypermedia. Because of the growing

importance new media have been acquiring in communication processes,

such a study is of high importance in order to assure the effectiveness

of communication. The fragmentation of contents and the absence

of a predefined reading order characterizing hypertexts and hypermedia

can affect the process of text coherence building and, therefore,

the interpretation and comprehension of the messages conveyed through

such artefacts (cf. Engebretsen 2000; Fritz 1999; Storrer 2002).

The hypermedia designer has to sustain the user in this process

by taking care of the signs he decides to include in the application.

In fact, as the semiotic engineering approach outlined (cf. De Souza

1993; De Souza et al. 1999; Prates et al. 2000), a successful user-application

interaction depends on the reader’s understanding of the designer’s

intentions and icons and messages constituting the user interface

have to be studied as signs. Correspondently, the interaction between

user and interface has to be studied as a process of signs interpretation.

In this paper we present the results of a research devoted to a

very precise aspect of this main topic, namely the use of a particular

kind of hypermedial applications in the field of literature and

literary studies and the conditions of its effectiveness.

0.2 Hypertext and literary studies

At

the beginning of the spreading out of hypertext several professors

and scholars underlined the advantages of the use of this new technology

and textual form for the study of literature. A vivid enthusiasm

accompanied the appearance of the first literary hypertexts. Since

then, different kinds of hypertextual and hypermedial applications

for literature can be found both on-line and off-line: archives,

hyperfiction, presentations of authors, presentations of themes,

presentation of literary works. The reason of the initial enthusiasm

was the belief that a technology had finally appeared that was able

to realize the poststructuralist principles and the principles of

deconstruction. 1This was particularly

evident in hyperfiction, but it was also related to new possibilities

for literature teaching and learning and, thus, to the uses of hypertext

for the educational presentations of different topics and subjects

for literary studies (authors, themes, literary works). Different

claims were made starting from the idea of this convergence between

hypertext and post-structuralism and deconstruction.2

The central and most striking claim had to do with the nature of

the reading experience. The literary text calls for reading and,

therefore, reading is at the core of literature and literary studies.

In the enthusiasm for the innovation introduced by hypertext, it

was claimed that this new textual form would bring a new way of

reading that, in the case of hyperfiction, was called “hyperreading”.

This new way should derive from the particular features of the hypertextual

form, especially from non-linearity. Non-linearity (or multilinearity

as it has subsequently been defined) was seen as the main hypertext’s

feature, the feature capable of breaking the unity, the stability

and the canonical order of the literary text, thus allowing the

reader to choose her/his own reading path through the text (Bolter

1991; Delany & Landow 1994; Joyce 1995; Landow 1997). In fact,

even if reading cannot be but linear – the reading of a word

after the other inevitably creates a linear sequence -, hypertext

is, at least at the potential level, multilinear, since several

different possible reading paths are made available (cf. Cantoni

& Paolini 2001; Liestøl 1994; Miall 1998; Rosenberg M.

1994).

In the work we are presenting here we aimed at verifying the truth

of this claim about hypertext reading by studying one particular

kind of hypertext/hypermedia for literature, namely applications

presenting a given literary work. We called them hypertextual transpositions

(henceforth HT). We analyzed examples of this particular kind of

technological artefact starting from a semiotic-hermeneutic perspective3

and this analysis allowed us to identify two main characteristics

of this kind of hypermedia having an impact upon the act of reading

the literary text. We will describe them in the following, after

having defined what HT are and how we approached them.

1. Defining hypertextual transpositions

HT

are hypermedial applications focussing on a given literary text.

They are meant to be used in reading, enjoying and/or studying the

literary text. Concretely, they consist of the electronic version

of the literary text (which constitutes the core of the application)

and of a series of added materials (that can be other texts, images,

video clips and audio files) that aim at casting light upon the

literary text’s significance and at enriching the reading

experience.

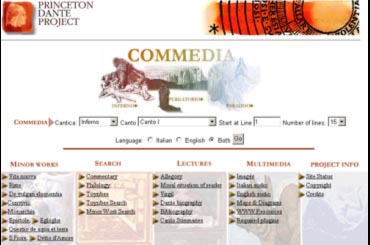

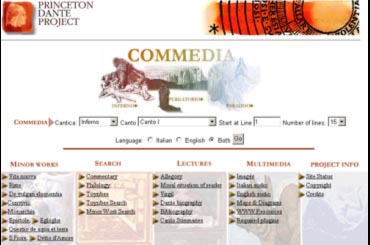

Fig. 1 – DC2 is an example of HT of the Divine Comedy. Here

the electronic version of the literary text is available in the

collection “Commedia” (which can be accessed from the

access device displayed in the upper part of the homepage). Added

materials (such as texts of other works by Dante, essays about different

themes developed in the Inferno, illustrations of the text, audio

files with aloud readings, maps of the Hell) can be accessed from

other collections, displayed in the low part of the homepage.

The

most interesting aspect of HT consists in the fact that they imply

the transposition in a new medium of a text that was originally

conceived for a different medium. For instance, Dante wrote the

Divine Comedy as a manuscript and since several centuries we have

been used to read it in a printed form (as a book). In DC2 (cf.

fig. 1) this text is transposed in a new medium, which essentially

is a hypertext.

In fact, HT are hypertexts and, therefore, they present all the

features hypertexts have. Namely, they are characterized by multilinearity

(which comes from the fact that contents are fragmented in nodes,

which are then connected through hyperlinks) and – usually,

except the contrary is specified – by the absence of a preferential

reading order. Several different reading orders are possible and

more or less equivalent. Referring to the above-described claim

concerning hypertext reading, we can wonder if and how these characteristics

hypertextual transpositions share with all kinds of hypertexts have

an impact on the act of reading the literary text. We can wonder

what happens when literary texts we are used to read in a printed

form are transposed in this hypertextual form.

According to a semiotic-hermeneutic perspective, HT have been considered

as the result of the adding of new signs to the signs of the literary

text. Consequently, their analysis was guided by the question “how

does the reader interpret the signs composing them?” and “which

contribution and which difficulties these new signs bring with as

to the literary text’s comprehension?” The comparison

of HT to printed annotated and/or illustrated editions (which we

considered to be HT ancestors, since they are the artefact in which

we are accustomed to read literary texts) also helped in identifying

HT most peculiar features.

Particularly, this comparison let emerge the presence in HT of two

main features, namely the increased presence of visual representations

of elements or aspects of the literary text (which we called logic

of representation) and the presence of signs (which can be contents,

devices or tools) influencing the way in which the literary text

is read (we called these elements second order representation).

From these features of HT derive new conditions for the act of reading

the literary text. First, the increased use of visual representations

(of images) as means to understanding entails risks of misunderstanding

as to the function of these images in respect to the literary text.

These misunderstandings can prevent the reader from reaching the

comprehension of the literary text’s significance. It is therefore

necessary to avoid the arising of such misunderstandings. Second,

the elements influencing the way in which the literary text is read

(the second order representation) have to be adequate in respect

to the reader’s goal and task; otherwise, such elements can

prevent the reader from reaching the literary text’s comprehension.

2. Main features of hypertextual transpositions

2.1 The logic of representation

Usually in HT a remarkable amount of images is used in

relationship to all the different aspects of the literary text’s

structure and significance. Images are used in relationship to philological

aspects, namely for the illustration of and the access to manuscripts,

folios or different versions of the literary text. But they are

also used for the description of characters and places (that is,

for the illustration of the geographical setting of the narrated

story; cf. fig. 2) and for the illustration of elements of the historical

context in which the literary text has been produced (such as images

of important characters of the time, of important places or important

events; cf. fig. 3).

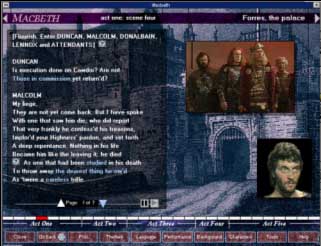

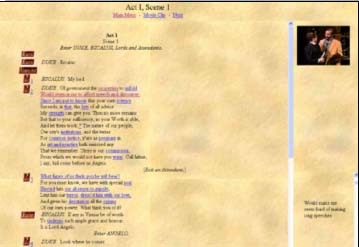

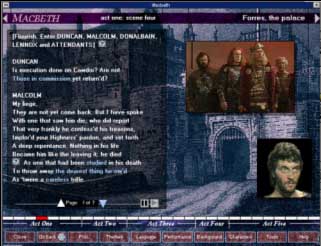

Fig. 2 – M1 – On the text’s screen photographs

of the speaking characters and a background representing the landscape

are present.

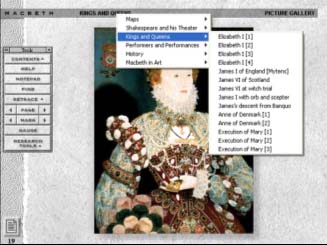

Fig. 3 – M2 – A gallery of images is

dedicated to kings and queens of England.

In

HT the literary text’s significance is highlighted for a great

part through visual representations. Several elements or aspects

of the literary text are presented and explained in a visual way.

In other words, in HT there is the use of a deictic modality, more

precisely of the modality of monstrare ad oculos, for the

clarification of the literary text’s significance. This modality

consists in contributing to the comprehension in allowing the user

to see the object s/he has to know in order to understand a given

word or passage of the literary text. We defined this modality as

“understanding by seeing” maxim.

The goal of the adoption of this maxim is providing the reader with

a more experiential knowledge and comprehension of the literary

text by providing her/him with the knowledge of the denotata.

This modality of providing access to knowledge and comprehension

brings for sure benefits for the reader. In fact, the reference

to denotata, that is, to the objects of the concrete world,

is essential to human communication and the perception of objects

is essential to human knowledge (it is essential for human beings

in order to acquire the knowledge of something).

It is important to point out that benefits derive from this practice

for the reader only if an essential condition is respected, namely

the condition of correspondence between the content of the image

and the content of the part of the literary text to which the image

refers. Our analysis showed that in HT this condition is always

respected. Nonetheless, the comprehension of the function of the

images in respect to the literary text is not always immediate.

This is due to the features of images as signs. Images are analogical

signs and as analogical signs they present some particular characteristics.

For instance, images are highly rich from a semantic point of view

(an image transmits at the same time a lot of information in a dense

way) and their perception is open to different possibilities. These

two features can be source of secondary meanings, which, in the

case of images referring to a passage of the literary text, can

go beyond the meaning of the passage the image aims at clarifying.

Because of this complexity and these features images as signs always

imply a level of interpretation that cannot be avoided and that

contrasts the attempt to provide to the reader a more direct and

experiential access to the literary text’s significance. In

other words, the interpretation images as signs require can entail

difficulties for the “understanding by seeing” maxim,

in that the reader cannot understand the function of the image in

respect to the clarification of the literary text’s significance.

Two other factors intervening in the process of image’s interpretation

contribute to these difficulties, namely the reader’s prior

knowledge (which, when it is rich, can make easier for the reader

the comprehension of the image and of the text) and the captions

of the images (the information it provides can guide the reader’s

attention on one aspect of the image instead of another).

Because of these difficulties misunderstandings can arise between

author/designer and reader as to the function of the image in respect

to the literary text’s significance. We take as an example

the images available in DC1 at Inferno I, 71.

Fig.

4 – DC1 – Images available correspondently to Inferno

I, 71 (“Nacqui sub Iulio, ancor che fosse tardi / e vissi

a Roma sotto 'l buono Augusto / nel tempo de li dèi falsi

e bugiardi”).

Inferno

I, 71 corresponds to the passage of the text where Dante met

Virgil, but he didn’t recognize him. Therefore, Virgil is

revealing Dante who he is. Particularly, he is saying that he lived

in Rome in the Antiquity. That is, Virgil is explaining the place

and the time in which he lived. Correspondently to this passage

of the text, in The World of Dante these four photographs of Roman

remains (forums, Colosseum and the Basilica of Constantine) are

available. These images aim at showing the place mentioned in the

literary text as it was at the time the literary text is referring

to. However, these images are photographs. Photographs have a strong

indexical character that establishes a connection with the actual

reality of the reader. Such a connection goes beyond the meaning

of the literary text. It is an added meaning, which however is not

part of what Dante wanted to communicate. The literary text puts

the accent upon the past, while the photographs added to comment

this passage put the accent on the present. The reader could interpret

them in a misleading way (“Oh, look at what there is in Rome!”),

without grasping the most relevant connection with the text. The

available captions (which read “Forums, Rome”, “Colosseum,

Rome” and “Basilica of Costantino, Forums, Rome”)

contribute in focussing the reader’s attention on this added

meaning, since they only provide factual information about what

is illustrated in the photographs and where it is placed. Of course,

if the reader’s prior knowledge about Rome, about the Roman

period and about Virgil is rich enough, misunderstandings about

the images’ function due to this secondary meaning can be

avoided.

The use of images can also entail another risk: the risk to induce

the reader to stop at the literal level of the literary text’s

significance (thus preventing him to carry on the inferential process

of comprehension in order to grasp also the levels of meaning that

go beyond the letter of the text, for instance the allegorical meaning).

2.2 The second order representation

Our

analysis revealed the presence in HT of contents, devices and tools

influencing the way in which the literary text is read. The presence

of these elements introduces a new condition for the act of reading

the literary text, which consists in the fact that these elements

have to be adequate in respect to the user’s goal and task.

Since they have an influence upon the way in which the literary

text is read, we consider these contents, devices and tools as signs

in respect to a way to approach the literary text. They are signs

in respect to a reading strategy. We defined a reading strategy

as a way to approach the text,4

to perform the act of reading the text. These elements are reading

strategies representations. All together they create a representation

that in the HT is superposed to the literary text (which is on its

turn a representation). For this reason, we called it second order

representation.

The presence or the absence in the HT of a given content, device

or tool has an impact upon how the reader approaches the literary

text. For instance, in DC3, the “I Canti” collection

centre consists in an index displaying all the cantos of the Inferno.

To each canto corresponds an icon with a detail of the image that

will appear at the bottom left corner of the literary text screen.

Rolling over each icon, information about the place and the time

the canto takes place is displayed at the bottom of the screen.

In this way, when entering the text of a given canto, the reader

already got essential contextual information (cf. fig. 5).

Fig. 5 – DC3 – “I canti”

collection centre and detail of the information appearing the lower

part of the screen.

Reading

strategies are a hierarchical concept. It is possible to distinguish

between high-level and low-level reading strategies. Low-level reading

strategies deal with a very precise and partial aspect of the act

of reading. They are represented by single contents, devices or

tools included in the HT. A combination of low-level reading strategies

represents high-level reading strategies, that is, reading strategies

dealing with more comprehensive aspects of the act of reading.

All the elements of the application we recognized in the analyzed

HT as having an impact on the way the literary text is read have

been classified according to the low-level and the high-level reading

strategy they represent. In this way, we obtained a picture of an

ideally complete representation of reading strategies in HT. Fig.

6 provides an example. On the basis of this classification, the

act of reading a literary text in HT can be defined as the result

of the combination of various reading strategies represented by

contents, devices or tools included in the HT.5

| High-level

reading strategy |

Low-level

reading strategies |

Devices |

| Situating

the part of the literary text the user is exploring within the

whole of the narration |

Being

aware of spatial and temporal coordinates of the events narrated

in a given part of the literary text |

Place,

date, time and main characters are displayed on each text screen |

When

on the text pages

[DC3, M1]

|

Before

entering the text pages (behaviour anticipation pattern)

[DC3]

|

| Visualization

of the place of the narrated event |

Map

with the indication of the place that corresponds to the narrated

events

[M2 interactive maps]

|

3D

View

[DC1] |

Screen

backgrounds

[M1, M3]

|

Illustrations

of narrated scenes

[DC1, DC2, DC3]

|

| Gaining

an overview on the whole narrated story |

Easy

access to maps and schemes from the literary text screens

[DC2, DC3, O1 (collection centre of “Incontri”)] |

Easy

access to a plot-line from the literary text screens

[M1, MD2] |

Easy

and immediate access to a synopsis

[M1 (from each text screen), M3 (already on the homepage, before

the reader enters the literary text screens), MD2 (from each

text screen), RJ1 (already on the homepage, before the reader

enters the literary text screens)] |

On

the literary text screens, access to the summary of the part

of the literary text to which the page the reader is exploring

belongs

[DC2, DC5, H1, M3, RJ1] |

On

the literary text screens, access to descriptions of the place

where the narrated events happen

[DC5] |

On

the literary text screens, access to summaries of the other

parts of the literary text

[H2 (even if it is less direct because the reader moves to another

collection), M1, M2, MD2, O1 (already on the homepage and before

entering the text!)] |

The

division of the text of a given part among several different

screens follows a semantic criterion, that is, it aims at reflecting

the sense of the text (not a fixed number of verses per screen,

but narrated episodes)

[DC3, H2] |

Fig.

6 – Example of classification of reading strategies representations.

In the right column are the detected devices. For instance, screen

backgrounds, access to maps and schemes. In the central column these

devices are grouped according to the low-level reading strategies

they represent. In the left column the low-level reading strategies

are grouped according to the high-level reading strategies they

contribute to represent.

However,

to classify contents, devices and tools present in the application

according to the low- and high-level reading strategy they represent

is not enough in order to clarify the new condition the second order

representation introduces on the act of reading literary texts in

HT. Besides the second order representation itself, it is necessary

to take into consideration the goal of the user of a HT and her/his

major task.

The goal of the user of a HT can be defined as the success of the

act of reading the literary text. In other words, the goal is the

literary text’s comprehension. Such a comprehension is reached

by the user in different ways, owing to the major task s/he has

(or wants) to accomplish. It is possible that the user has or wants

to read the literary text, to study the literary text or to conduct

some specific research on the literary text. These are three different

user’s tasks, which can also be viewed as three different

modalities in which the act of reading the literary text (which

remains the basic activity in HT) can be carried out. Reading the

literary text refers to immersive reading, that is, to the kind

of reading that is considered to be characteristic of literary reading

and that places at the core of the act of reading the interaction

between text and reader’s images, memories and desires. Studying

the literary text refers to a situation where the reader needs to

acquire a systematic knowledge about the literary text. Researching

the literary text refers to a situation where the reader uses the

hypertextual transposition in order to build a knowledge that was

not made explicit by the authors in the HT contents.

For each HT it is possible to define the user’s goal and task.

Concretely, the user’s major task appears from the information

provided in the HT itself. Sometimes, it is explicitly declared.

Sometimes, it has to be defined on the base of its intended audience.

For instance, if the intended audience of a given HT is composed

of students, it is likely that the major user’s task is studying

the literary text.

User’s goal and task allow us to define the adequacy of the

second order representation. In fact, we can now say that a reading

strategy is adequate when it allows the reader to reach the goal

by accomplishing the major task. What counts is the adequacy of

the second order representation, not the second order representation

itself.

From these considerations a model of the act of reading a literary

text in HT can be derived, that highlights the adequacy of the represented

reading strategies (cf. fig. 7). The act of reading the literary

text in HT can be conceptualized as a pyramid, the vertex of which

is the literary text’s comprehension (that is, the user’s

goal). The user’s major task coincides with the perimeter

of the pyramid. The reaching of the vertex within a given perimeter

is allowed by a combination of reading strategies represented in

the hypertextual transposition. The pyramid surface coincides with

the combination of represented reading strategies (in fig. 7 each

number identifies one of the detected high-level reading strategies).

The reaching of the literary text’s comprehension depends

on the representation of the combination of reading strategies,

which is the most adequate considering the major task the user has

to accomplish.

Clic

on image

Fig. 7 – Model of the act of reading a literary text in HT.

As

a consequence, we can say that the importance of each high-level

reading strategy depends on the major user’s task. For instance,

if the major user’s task of a given application has been identified

as being “reading the literary text”, strategies 3.1

(“paying attention to the literary text”) or 4 (“getting

immersed in the reading experience”) are important, while

they are less important if the major user’s task is studying

the literary text or researching the literary text. Therefore, the

second order representation of this HT will be considered adequate

only if reading strategies 3.1 and 4 are widely and clearly represented.

Only if this happens, the second order representation assures the

success of the act of reading. If the major user’s task is

studying the literary text, strategies 2.2 (“integrating information

provided by added materials and annotations with the meaning of

the passage of the literary text it refers to”) and 3.3 (“exploring

further information”) will be important and, therefore, their

wide and clear representation within the application will be essential.

If the major user’s task is researching the literary text,

strategy 5 (“investigating the literary text according to

‘personal’ needs or questions”) and their adequate

representation will be important.

Comparing HT and printed editions of literary texts as to the presence

of a second order representation, we notice that, to a certain extent,

reading strategies representations are also present in printed editions

of literary texts. It is for instance the case of indexes, which

are devices that can have an influence upon the way in which the

text is accessed. However, in printed editions, mainly reading strategies

remain implicit. In HT their representation is of higher importance.

There, reading strategies that are usually implicit when reading

the literary text in a printed form, have to be made explicit, that

is, they have to be represented.

The reason of the major importance reading strategies representations

have in HT comes from the above-described two main characteristics

of hypertext, namely the physical fragmentation of contents and

the particular presupposition of hypertext. Since contents are fragmented

and since no canonical reading order is presupposed, the reader

needs more explicit devices in order to build the coherence during

the act of reading. In a printed edition such elements are implicitly

present on the base of the presupposition that the reader will begin

her/his act of reading from the beginning of the text towards its

end. The reading strategy in the case of a printed text is taken

for granted, while in a hypertext (more specifically, in a HT) it

is not, since there this presupposition drops. This could simply

be a cultural problem (we are not yet used to HT), but it could

also be a technological one (a problem deriving from a feature of

the medium).

The higher importance reading strategies representations have in

HT in respect to printed editions is proved by the fact that the

non-explicitation of given reading strategies creates an obstacle

preventing the reader to put this reading strategy into effect.

This means that their non-representation can prevent readers from

an effective act of reading. It is for instance the case of the

use of scrolling menus in the text’s collection. They prevent

the reader to have an overview upon the whole content of the collection

and, therefore, upon the position of a given scene in respect to

the whole (cf. fig. 8).

Fig. 8 – M3 – Use of scrolling menus.

Another

example is constituted by situations in which, once the reader entered

the literary text collection, only the possibility to move forward

in browsing the literary text is represented. This prevents him

to move back, to previous pages (cf. fig. 9). This is absolutely

impossible in a printed edition.

Fig. 9 – MD1 – Text screen and detail showing that the

reader can only move forward.

Both

the explicitation of reading strategies and their adequacy in respect

to the user’s goal and task constitute essential conditions

for the success of the act of reading literary texts in HT. The

second order representation has to be adequate.

A key-point of the second order representation is constituted by

the interpretation of hyperlinks. This is for two reasons. First,

in order for the reader to adequately perform a given reading strategy,

it is necessary that the access to such contents appears meaningful

to him. The reader needs to grasp the semantics of the hyperlink,

to understand to which content the link provide access. For instance,

in order to adequately perform reading strategy “Gaining an

overview on the whole narrated story”, it is necessary that

the link providing access to a map, a scheme or a text summarizing

the story appears clear to him. Second, understanding the semantics

related to each type of link available in the HT allows the reader

to become acquainted with certain rules lying at the base of the

application. The knowledge of these rules allows the reader to perform

the adequate reading strategy. The performance of the adequate reading

strategy depends on a regularity that the reader can perceive only

in observing the signs made available by the author/designer.

In order to clarify the working of this crucial point of the second

order representation, we studied hyperlinks from a semiotic point

of view, by describing them as signs and by describing the process

of interpretation the user has to perform in front of them.

“Hyperlink” signs are composed of an anchor (the perceptible

part of the link, its strategy of manifestation) and of a function,

which is the signified, the meaning. But hyperlinks as signs are

characterized by the fact that within the link’s meaning two

layers can be distinguished. First, the link is a proposal, an invitation,

of the author for the continuation of the communication. Second,

this proposal of the author contains a promise of relevance.

Because of the presence of these two layers within the link’s

meaning, when interpreting a link, the user always has to apply

at the same time two of processes of interpretation: one in order

to identify the link as an invitation, a proposal, and another one

in order to understand its relevance. The process of interpretation

the user uses in order to interpret the link as an invitation is

always an indexical process. This means that the user’s reasoning

is the following “Since this word is underlined in blue colour,

here there is a possibility to go on in the communication”.

The process the user uses in order to interpret the relevance can

be an indexical, but also an iconic or a symbolic process of interpretation.

For instance, “Since the word ‘Virgilio’ is underlined

in the literary text, clicking there, I will get information about

who Virgil is”. These two different processes of interpretation

are interlaced. Usually the first one is not problematic, it is

almost automatic, while the second one is difficult; it is the one

where misunderstandings can occur.

In the analyzed HT we noticed that two modalities are used in order

to avoid such misunderstandings. First, iconic processes of interpretation

(which are the most risky ones) are avoided by making available

in HT links requiring only indexical or symbolic processes of interpretation.

Second, the reference to common practices of the field of literary

annotation and criticism are exploited in order to make the hyperlink’s

interpretation easier. For instance, the underlined words or expressions

used in fig. 10 exploit a common practice in literary criticism.

In fact, also in footnotes of printed editions usually happens that

different kinds of comment are provided and the reader cannot predict

which kind of comment he will find by reading the footnote.

Fig. 10 – MM1 – Underlined words or

expressions as hyperlinks.

As

it is for the explicitation of reading strategies and for their

adequacy in respect to the user’s goal and task, also the

use of anchors for hyperlinks avoiding processes of interpretation

that can be misleading is an important condition for the success

of the act of reading literary texts in HT.

3. Conclusions

The

adopted semiotic-hermeneutic perspective allowed us to identify

two main features of HT entailing risks for the effectiveness of

their use, namely for the success of the user’s process of

interpretation and comprehension. Such findings alert HT designers

to take care, on the one side, of the use of images as explicative

means in the perspective of the user’s understanding of the

function of these images in respect to the literary text and, on

the other side, of the adequacy of the second order representation

in respect to the user’s goal and tasks.

Beyond HT, this semiotic-hermeneutic perspective could be fruitfully

applied to other kind of hypermedial applications. Our first step

toward this direction of research (we applied this perspective to

hypermedial applications dealing with health communication topics;

cf. Mazzali-Lurati & Schulz 2003) proved to provide interesting

findings.

Notas:

1

The first works on hypertext and literature make constant reference

to theorists such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida and Michel

Foucault. Cf. Bolter 1991, 2001; Joyce 1995; Landow 1997.

2 They ranged from the claim that

hypertext has an associative nature that reflects the way in which

human mind works better than printed texts, to the claim that hypertext

provided new possibilities for literature teaching and learning,

bringing students to become more active (for instance, by allowing

them to contribute to the creation of the hypertext itself by adding

new connections to the ones established by the hypertext’s

author or by learning from the reasoning that led the teacher or

the expert to create given connections) (cf. particularly Landow

1997).

3 In our study we analyzed seventeen

hypertextual transpositions, devoted to different genres of literary

texts, namely hypertextual transpositions of Dante’s Divine

Comedy, some of Shakespeare’s plays (Hamlet, Macbeth and A

Midsummer Night’s Dream), of Homer’s Odyssey, of Boccaccio’s

Decameron and of Mary Shelley’s The Last Man. In the following

all the analyzed applications are indicated through abbreviations.

Complete references are provided at the end of this paper in the

References section.

4 We assume that the act of reading

entails two levels: an operational level and a semantic-cognitive

level. The operational level has to do with the manipulation of

the artefact, while the semantic-cognitive level has to do with

the understanding of the text. Reading strategies have to do with

both levels; they allow the reader to manage these two levels in

order to reach the literary text’s comprehension.

5 It is important to assure the

reader the possibility to perform these reading strategies. In order

to help this, we identified for each reading strategy a design pattern.

That is, for each reading strategy a reusable design solution has

been identified, the aim of which is to overcome the difficulties

preventing readers from adequately perform reading strategies. For

instance, to reading strategy 2.1 “situating the part of the

literary text the user is exploring within the whole of the narration”

corresponds a design pattern “sustaining the reader’s

orientation within the whole of the narration” that proposes

as a solution an easy access to devices such as summaries, plots,

schemes, etc.

Referencias:

Bolter,

J.D. (1991) Writing Space: the computer, hypertexts, and the

history of writing. Hillsdale (NJ), L. Erlbaum Associates.

– (20012, 1991) Writing Space: Computers, hypertext, and

the Remediation of Print. Hillsdale (NJ), L. Erlbaum Associates.

Cantoni, L. & Paolini, P. (2001) “Hypermedia Analysis:

Some Insights from Semiotics and Ancient Rhetoric”, Studies

in Communication Sciences – Studi di scienze della comunicazione

1(1), 33-53.

Delany, P. & Landow, G.P. (eds) (1994) Hypermedia and Literary

Sudies. Cambridge-London, MIT Press.

De Souza, C.S. (1993) “The semiotic engineering of user interfaces

languages”, International Journal of Man-Machines Studies

39, 753-773.

De Souza, C.S., Prates, R.O. & Barbosa, S.D.J. (1999) “A

Method for Evaluating Software Communicability” in IHC’99

Proceedings. Campinas, SP, Brazil. October, 1999. (CD-Rom).

Available at <http://peirce.inf.puc-rio.br/production.php>.

Engebretsen, M. (2000) “Hypernews and Coherence”, Journal

of Digital Information 1(7). Available at <http://jodi.ecs.soton.ac.uk/Articles/v01/i07/Engebretsen>.

Fritz, G. (1999) “Coherence in Hypertext” in Coherence

in Spoken and Written Discourse by W. Bublitz et al. (eds), 221-232.

Amsterdam-Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Joyce, M. (1995) Of two minds: hypertext pedagogy and poetics.

Ann Arbor, University Michigan Press.

Landow, G.P. (1997) Hypertext 2.0. The Convergence of Contemporary

Critical Theory and Technology. Baltimore-London, John Hopkins

University Press.

Liestøl, G. (1994) “Wittgenstein, Genette, and the

Reader’s Narrative in Hypertext” in Hyper/Text/Theory

by G.P. Landow (ed.), 87-120. Baltimore-London, Johns Hopkins University

Press.

Mazzali-Lurati, S. & Schulz, P. (2003) “The actualization

of reading strategies in hypermedia”, Document Design 4(3),

246-268.

Miall, D. (1998) “The Hypertextual Moment”, English

Studies in Canada 24, 157-174. Online preprint version available

at <http://www.ualberta.ca/%7Edmiall/essays.htm>.

Prates, R.O., Barbosa, S.D.J. & De Souza, C.S. (2000) “A

Case Study for Evaluting Interface Design through Communicability”

in Proceedings of the ACM Designing Interactive Systems DIS’2000.

Brooklyn, New York. Available at <http://peirce.inf.puc-rio.br/production.php>.

Rosenberg, M.E. (1994) “Physics and Hypertext: Liberation

and Complicity in Art and Pedagogy” in Hyper/Text/Theory

by G.P. Landow (ed), 268-298. Baltimore-London, Johns Hopkins University

Press.

Storrer, A. (2002) “Coherence in text and hypertext”,

Document Design 3(2), 157-168. Preprint available at <http://www.angelika-storrer.de/>.

Analyzed

hypertextual transpositions:

D1)

The Decameron Web. Available at <http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Italian_Studies/dweb/>.

DC1) The World of Dante. Available at <http://www.iath.virginia.edu/dante/>.

DC2) Princeton Dante Project. Available at <http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/index.html>.

DC3) La Divina Commedia: [Inferno]: un viaggio interattivo alla

scoperta del capolavoro dantesco, Milano, Rizzoli New Media,

cop. 2001.

DC4) ILTweb Digital Dante. Available at <http://dante.ilt.columbia.edu/>.

DC5) Webscuola – L’Inferno dantesco. Available at <http://webscuola.tin.it/risorse/inferno/index.htm>.

H1) Webscuola – Amleto. Available at <http://212.216.182.159/risorse/amleto/>.

H2) Hamlet on the Ramparts – MIT. Available at <http://shea.mit.edu/ramparts/>.

LM1) The Last Man by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. A Hypertext Edition

by Steven E. Jones. Available at <http://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/mws/lastman/index.html>.

M1) BBC Shakespeare on CD-ROM. Macbeth, London, BBC Education:

HarperCollins, cop. 1995.

M2) Macbeth, The Voyager Company, cop. 1994.

M3) William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Bride Digital

Classic, Bride Media International, cop. 1999.

MD1) Midsummer Night’s Dream – Lingo.uib, Universitetet

i Bergen. Available at <http://cmc.uib.no/dream/index.html>.

MD2) BBC Shakespeare on CD-ROM. A midsummer night’s dream,

London, BBC Education, HarperCollins, cop. 1996.

MM1) Interactive Shakespeare. Available at <http://www.holycross.edu/departments/theatre/projects/isp/>.

O1) Odissea, Milano, Rizzoli New Media, cop. 2001.

RJ1) William Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, Bride

Digital Classic, Bride Media International, cop. 1999.

Sabrina

Mazzali-Lurati

Graduated in Italian literature at the “Faculté

des Lettres” of the University of Fribourg,

Switzerland.

Peter Schulz

Professor of Semiotics and Vice-director of the

Linguistics-Semiotics Institute of the School of Communication Sciences

at University of Lugano, Italia. |