Comunicación en la Vida Cotidiana

Número 6, Año 2, febrero-marzo 1997

Building Brands in a Global Marketplace

By: Diane Perlmutter

Chairman, US Marketing Practice

Burson -Marsteller

Thank you. I'm here today to talk about building brands in a global marketplace. I am wearing Armani suit, using Kodak slides created on a Toshiba laptop, sipping a glass of Santa María water.

And I would venture to guess that my four brands - 1 American, 1 Japanese, 1 Italian and 1 Mexican are similar to the mix of brands that each of us uses at any given time. Because, today, everyone is a dual citizen first in the country of his or her birth, and, second, in the global marketplace.

And like most citizens, we all speak the language. Let me explain what I mean. The average consumer recognizes over 5,000 brands. Linguists agree that you can speak a foreign language when you know a minimum of 5,000 to 6,000 words. Thus, in addition to our mother tongue, we all speak another language: the language of brands. And brands, just like words, are verbal representations of physical characteristics, objects, concepts, relationships and images.

So, in a world where everyone is so aware of brands, why is it that some brands thrive while others merely survive? The answer is perception.

As we market our products and services going into the 21st century, it is important to remember that just having a good product isn't always going to be good enough.

Because a product is just the sum of its attributes and benefits. While a brand is the perception of those attributes and benefits.

For example, cola is a brown-colored, sparkling, pleasant tasting beverage. Coca-Cola is a fun, contemporary experience.

An automobile is a 4-wheeled vehicle that transports people. A Ford is a high quality, well-designed, stylish way to travel.

So when consumer goes into a store looking for a product, she ends up buying a brand.

Today, more than ever, corporations are realizing that their brands are an important asset on their corporate balance sheets. Instinctively they've always known that, but recently the value has been quantified at the time of purchase. In 1989, Philip Morris paid $12.9 billion for Kraft. In 1994, Gerber sold for $3.7 billion for Snapple for $1.7 billion. These and other brands are worth billions, so managing and building them is a high priority for all companies.

Today, I want to cover two major areas. First, the theory of brands and brand-building. Second, some ways that large and small companies can successfully build brands around the world.

Let's start with a definition.

This is not as easy as it seems. A brand can be defined from a legal standpoint, a communications standpoint or an accounting standpoint... and even within each discipline, there is no agreement.

The Dictionary of Advertising Terms says a brand is "an identifying mark, symbol, word(s) or combination of same that separates one company's products or services from another firm's..."

I guess that«s okay, but for today, at least, let«s agree on this one:

A brand is "a differentiating promise linking the product with the consumer, assuring the consumer that the product will provide consistent quality and superior value, thus convincing the consumer to pay a higher price for the brand than for others in that product category".

The history of brands is really quite long. The first recognized brands were actually the early marks printed by Romans on tiles to sign their production.

In more recent history, brands flourished with mass production, as early entrepreneurs put their names on the packages of their products. In those days, consumers formed their perceptions of a brand based on their own experiences using the product, or the experience of people they knew.

The ability of the product, itself, to meet a consumer«s need was the most critical criterion for success of the brand.

Then companies began to advertise and consumers had a perception of the brand before they even made the purchase. Through advertising, brands function as signals.

In the 50«s they signaled quality Ivory Soap, for example. In the 60ís, brands often answered specific needs like Volkswagen and "small is beautiful". In the 70ís, brands represented a lifestyle like the Pepsi generation. And in the 80«s, it was values as exemplified by Apple Computers and other power to be your best".

Brand advertising in the 90«s has been an amalgam of previous decades with no clear differentiation, other than one trend to me, a troubling trend that I call dis-advertising: cynical, sarcastic, put downs of people and products. But that«s a different topic...

With the advent of advertising, if the product delivered on the promise of the brand, then the perception remained in place, the consumers repurchased, and the brand thrived.

The next evolution of brands is still a work-in-progress. While there are examples of multi-national companies selling brands in different countries since the end of World War I, the strong push for global marketing began somewhat later. As companies began to more aggressively expand internationally in the 70's and 80's, they were faced with a number of alternatives.

One of the most important decisions a company's marketing team had to make was should the product carry the same brand name and images as it did in its country of origin? Or should it be renamed and redesigned for the market into which it was entering?

There are successful examples of both decisions even within one company! Like Procter & Gamble with some detergents using different brands and imaging around the world while some shampoos are the same in every country in which they are sold.

The brand decision was not unlike the broader decision every company was making at that time: should authority be centralized or decentralized?

Frankly, I believe the corporate decision was much less important than the brand decision. In fact, many companies reorganized on a regular basis, flipping back and forth between having authority resting in local companies versus centralizing it with management in corporate headquarters. I know that many of you who work for large multi-nationals can probably remember at least 2 or 3 directives and reorganization memos.

I don't mean to be disparaging of companies who made these changes. Globalization was new and we were all learning.

But while companies could reorganize with minimum impact on their consumers, brands could not.

Once a brand had been named, positioned, packaged and promoted, it had created a perception among its target audience that would be difficult to change.

We can all name the brands that did it best: Coca-Cola, Kodak, Ford, DuPont. These brands are icons. They grew and flourished in a different time. And their stones are told in every marketing textbook ever written.

Today Iíd like to look at how brands are growing in the cluttered global marketplace of I 996. A marketplace where in the US, last year, there were over 11,000 new products introduced. Where, in France, 100 new items appear on supermarket shelves ... every day.

In a marketplace where companies, attempting to find profitable niches in which to sell their products, often create a sub-brand and a sub-sub brand--over-extending and splintering the brands whose sheer monolithic consistency and fortitude had made them successful.

The result of this excessive proliferation of brands? It is much harder to build a brand today than it has ever been before.

So how do you build a brand? What makes it strong?

Conventional wisdom was that to build a brand, one needed to create high levels of awareness. Today, we know that while awareness is certainly important, it is not what is needed initially to build enduring, powerful brands.

Beginning in 1993, Young and Rubicam, the global advertising agency--and the parent company of Bursoo-Marsteller--fielded the first wave of the largest study of brands ever done, Brand Asset Valuator. They interviewed 33,700 people in 24 countries and asked them about 8,000 brands, of which 450 of the brands were global or sold in more than one country. Here in Mexico, for example, over 750 brands were rated by 1,000 consumers.

Each brand was then ranked on the primary aspects that make up a successful brand: differentiation, relevance, esteem and knowledge. Differentiation and relevance equal the brand's strength while knowledge and esteem comprise the brand's stature.

The study found that the most successful brands received high ratings in all aspects, as they had expected. But the results of Brand Asset Valuator surprised them and challenged everyone's earlier thinking when it came to how the brand actually progressed.

The research showed that, independent of their product category, all brands developed in a very specific progression of consumer perceptions.

Differentiation is the engine of the brand train and is established first. Without differentiation consumers have no basis for selection and manufacturers have no reason to expect loyalty.

If a brand is not differentiated, its value equation is dominated by price rather than by benefit delivery. Simply put, an undifferentiated brand is really a commodity.

These are the top 20 brands in Mexico on the basis of differentiation. I should point out that part of the study included countries as brands as well--note that Mexico is highly differentiated here, as it is in other parts of the world. This learning has been important to us in our work promoting tourism on behalf of Sectur.

Successful new brands have high differentiation and lower levels of other aspects.

And, just as differentiation is the first thing that is built, when a brand fades, it is because it is no longer seen as differentiated. If differentiation is the engine of the brand train, if the engine stops, so will the train.

Once there is differentiation, a brand can evolve to the next aspect.

Relevance is a brand's personal appropriateness to its target consumer.

In a marketing context, differentiation yields a brandís margin opportunity while relevance yields the usage--or penetration--opportunity. The more relevant a brand is, the larger its audience will be.

Here's a quick look at the top 20 brands in Mexico based on relevance.

Differentiation and relevance are both an internal perceptions, while the next aspects are very much externally-driven.

Esteem comes next as a brand evolves. It is directly related to the perceptions of high quality and increasing popularity.

To me, one of the most interesting findings of the Brand Asset Valuator was the cultural differences in how esteem was comprised. With countries as diverse as Poland and China ranking popularity more than twice as important as quality--and Netherlands being at the other end of the spectrum. Mexico is fourth from the left with popularity more irmportant.

Now, let's look at brands in Mexico ranked by esteem.

Finally, knowledge is the successful outcome, the culmination of brand building. After establishing relevant differentiation, after achieving high esteem, then a brand can achieve knowledge among its consumers. It is important to note that knowledge is not just the result of a large advertising budget, knowledge is achieved, not bought.

Let's look at how some specific Mexico brands fare on Brand Asset Valuator.

One final point on BAV, it is interesting to note that no Mexican brands showed up in other countries--so there is significant opportunity for global growth.

We've looked at the theory of brand- building, now let's focus on the practice.

What are some of the ways that brands are being successfully built today?

First create differentiation for your brand, a unique position in the market place.

I cannot emphasize enough the importance of research in this regard. Don't speculate about who your customers are and how they perceive your brand. Conduct research and know for sure.

Use this knowledge to build highly targeted programs that show your brand at its best advantage like this one did.

DuPont wanted to increase sales of Tyvek in its graphic arts market segment at a time when awareness of Tyvek among printers and converters was fairly low. Those who were aware, knew it only as the tear-resistant material FedEx envelopes are made from In reality, Tyvek can be used for almost any printing job--from banners, tags and labels to jackets, shower curtains and costumes.

In addition to low awareness, there were negative perceptions in the marketplace as well. Some potential customers believed that Tyvek was difficult to print on and unsuitable for their needs. And, Tyvek was more expensive than other paper and fabric alternatives.

The solution was surprisingly simple. Instead of relying on media and promotional vehicles to report on Tyvek's printing capabilities, actually show the capabilities!

The company and their public relations agency decided to write and design a four-page newsletter and print it on Tyvek, highlighting, through examples, the brand's outstanding printing results. It also showed the tear- and water-resistance of Tyvek, as well as the material's ability to be cut sewn and converted into any size, shape or form.

The newsletter was so successful in building business in the US that it is now being distributed globally in English-speaking markets. And in 1995 the newsletter won a bronze medal in the largest printing contest in the United States.

Second, to build a brand, you must have a clear, consistent and integrated communications strategy, or more fundamentally, there must be a corporate mindset that ranks communications as important as R&D, finance and other core business skills.

The brand management team must look at all communications vehicles. What is said to the consumer--and where it is said--are as important as how often.

If your advertising says one thing your promotional, sponsorship and public relations efforts must be consistent. Each of these disciplines creates contacts between you and your publics. Integrated marketing isn't about having public relations match the ads. It's about having the brand live up to one promise that is delivered at each and every contact.

This is especially important because of the vast sums of money being spent by companies on brand communications.

Just two weeks ago, Advertising Age, the premier rnagazine of the United States advertising industry created a separate international edition to discuss global marketing. Among the information in that issue was the startling fact that between 1995 and 1996 the top fifty global advertisers increased their spending in markets other than the US by an average of 19.3%.

And in Burson-Marsteller offices around the world, we have found that companies are spending more on public relations, as well.

Integration is key to brand success. Let me tell you one way the Guiness Import Company did it extremely well.

In North America, around St. Patrick's Day, many beer companies feign Irish ôrootsö and plaster shamrocks and leprechauns on point-of-sale and advertising materials. Guinness' objective was to develop a program with enough impact to cut through holiday clutter, while emphasizing the brandís authentic Irish heritage.

The program needed to capture the public's imagination, be consistent with the brand's premium perception, and as is often the case, be done within a budget that was smaller than their competitors. Guinness and its agencies developed a program where a consumer had the chance to win an authentic pub in the town of Cobh, Ireland.

The key to this program's success was that it leveraged all communications tools available: advertising, public relations and promotion. This was done by awarding the prize based on a contest, rather than a sweepstakes, since sweepstakes rarely attract editorial coverage. In addition, this enabled them to ensure that participants had some relationship with the product since entrants had to describe their "perfect pint of Guinness" in 50 words or less.

Did it work? Absolutely. Sales of Guinness grew dramatically during the period of this promotion (up more than 20 percent) and distribution gains were significant. The program earned worldwide attention and talk-value for Guinness.

In this program. Guinness also did something else that was very important for building a successful brand. They created a powerful, personal link to the target.

Sometimes this means identifying allies to help carry your messages. When Gerber, the baby food company, wanted to sell their brand in Poland, they realized they couldn't do it alone. They teamed  up with the newly-formed Polish human services agency to help educate potential consumers about the health advantages of good nutrition and a balanced diet for baby. And, in the process, they built a bond with consumers and credibility for the Gerber brand.

up with the newly-formed Polish human services agency to help educate potential consumers about the health advantages of good nutrition and a balanced diet for baby. And, in the process, they built a bond with consumers and credibility for the Gerber brand.

Building the credibility bond using third party allies worked for them. Xerox, on the other hand, went inside for credibility in order to positioning itself as The Document Company. In the UK they have spent the last year introducing key Xerox product development staff to the media as experts. By communicating the knowledge and expertise of the staff, Xerox became the ultimate expert--an important customer linkage for building a brand.

Another way to build this bond is to relate the brand in the mind of the consumer to an important external event.

Two years ago in the US, the government passed new regulations for food labels. The National Label Education Act,or NLEA. The new labels were designed to give consumerís nutrition information to enable them to make more educated purchase decisions. So NutraSweet, whose success is based on consumers looking for their familiar swirl on the label, built a program around the NLEA--a campaign based solely on looking at labels. The result: NutraSweet helped support a key government initiative as well as its own brand-building strategy.

Barilla, the leading Italian food company, faced attacks from activists about the validity of Barilla claims that the wheat they used in their pasta was environmentally appropriate. Barilla decided to reach out to Legambiente, the most important Italian environmental association.

The goal was to identify mutual interests and develop programs that were important to both organizations. The partnership resulted in a three-year nutrition and environmental education program for school children The result: the Barilla brand became synonymous with caring. Caring about families, nutrition and the environment and sales continue to grow.

Finally, to build your brand, you must understand and manage global communications technology.

The single greatest impact on perceptions is the media and the accelerating speed of media communications has been awesome. Consider this.

When Abraham Lincoln made his Gettysburg address, it took about two weeks before everyone in the in the US had an opportunity to learn about this momentous speed. Jump ahead 100 years. When John Kennedy was shot in 1963, the entire world knew about it in two hours. And less than 30 years after that, in 1991, people in every city, in every country, watch the Gulf War take place complete with logo and theme song. CNNís global network revolutionized how we get information.... from two weeks to two hours to two seconds.

This technological advancement has a major impact on the publicís perception of brands, of institutions and of industries. If, in the past, a brand had a problem in one country, it remained there. At worst, a day or two later a small blurb might appear in another countryís media. Today, whatever happens in Acapulco or Amsterdam, in Cancun or Cairo, is broadcast around the world instantly and repeatedly.

Similarly, good news travels fast, as well. And positive words in one country can magnify and build a promise for a brand in other countries, as well.

Building a brand today is not always an easy task. But it can definitely be done. It takes building differentiation for the brand and it takes an integrated communications strategy. It requires that you understand the consumer and build a personal linkage to him or her. And it takes understanding the changing world of global communications. But most of all it takes what it has always taken: consistent strategy and brilliant execution.

Thank you.

Créditos Fotografías:

"Flor de manita" Tina Modotti, 1925.

Regreso

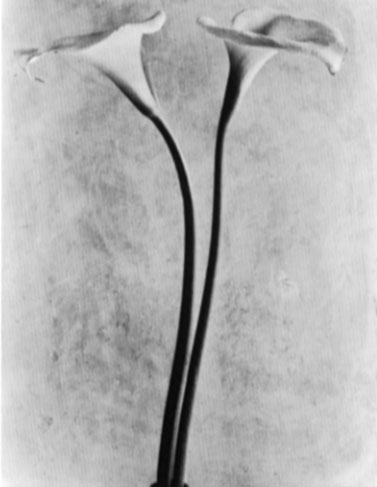

"Alcatraces" Tina Modotti, 1925.

Regreso